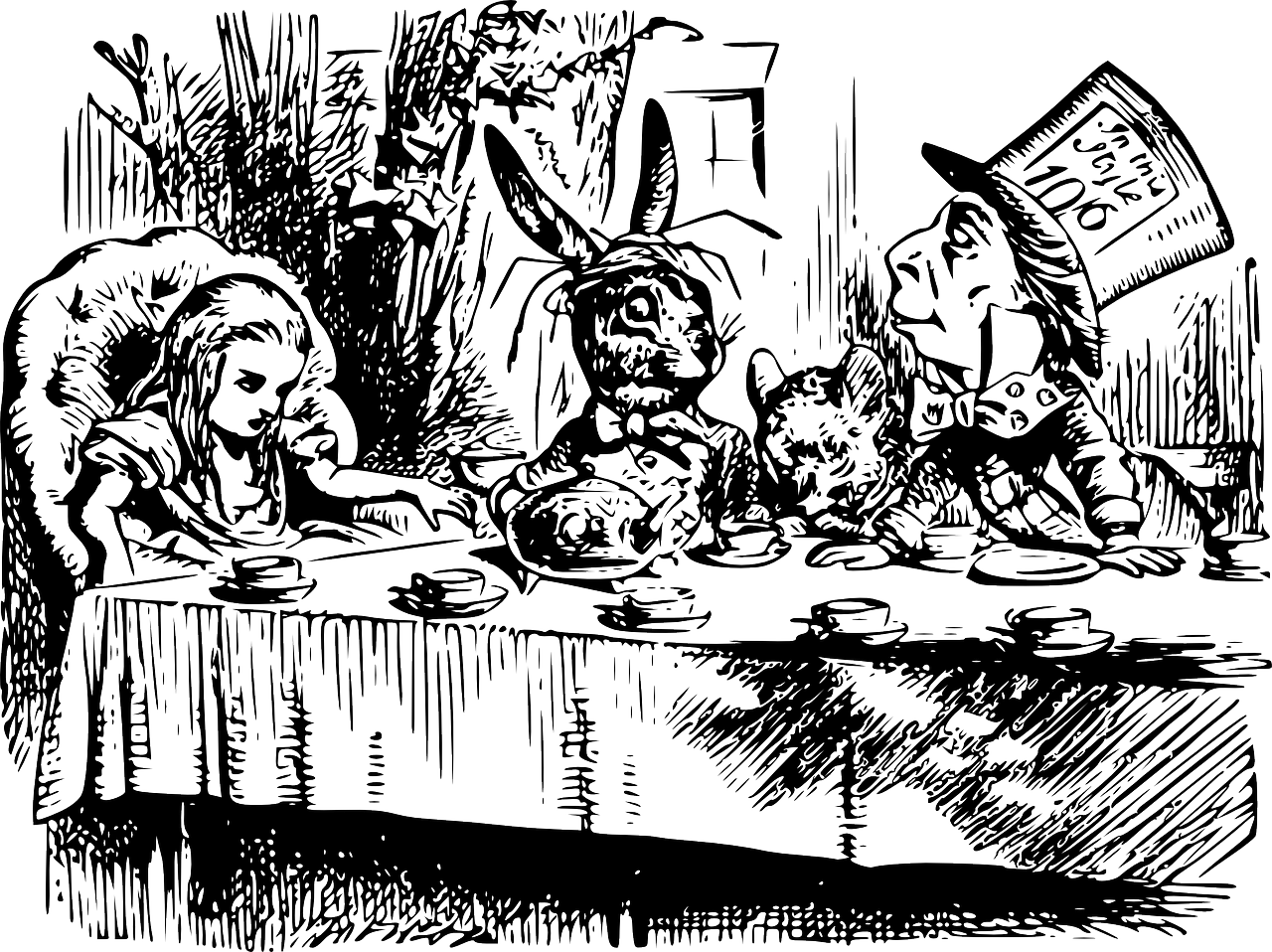

‘Do you mean that you think you can find out the answer to it?’ said the March Hare. ‘Exactly so,’ said Alice. ‘Then you should say what you mean,’ the March Hare went on. ‘I do,’ Alice hastily replied; ‘at least — at least I mean what I say — that’s the same thing, you know.’

Alice in Wonderland, Lewis Carroll.

Whilst fantastical, as well as humorous and entertaining, Alice‘s conversation with the March Hare is a fairly commonplace example of the sort of misunderstandings – and frustrations – that often occur in a dialogue of two differing styles!

Language is a behavioural system, and we have many different tools at our disposal in this system: voice, facial expressions, gestures. These and other elements of someone’s conversational style give us clues as to how the other feels about what they‘re saying.

Distinct from the words spoken, Deborah Tannen, Professor of Linguistics at Georgetown University, refers to these as metamessages in her book “That’s Not What I Meant‟ (1996).

A basic tool for signalling meaning is pitch shift; it can change the metamessage of the words spoken. Like loudness and softness, pitch can signal things like relative meaning, emotions and taking turns to speak. For example, pitch going up at the end of a sentence can make the sentence into a question, but it can also show uncertainty, or that you‘re asking for approval (unless you‘re Australian!).

A fall in pitch at the end of a sentence, conversely, signals finality and implies certainty. As meanings can be confused, these are useful tools to be aware of and use to your advantage. Seemingly minor phenomena can cause major disruptions and misunderstandings in one-time-only or day-to-day conversations.

Language expresses how we balance involvement with independence in the world; it can be a means of expressing power or showing solidarity. When a conversation doesn‘t seem to be going well, making minor adjustments in volume, pacing or pitch – speeding up or slowing down, leaving longer pauses or shorter ones – can enable us to get closer to a shared rhythm, which conveys collaboration and synergy rather than antagonism and competition.

Your conversational style can make the difference between being heard and being taken seriously, or not. It starts with self-awareness. Research of the type conducted by Professor Tannen and her peers has shown that women have a harder time being heard in the workplace than men, even when in positions of authority.

In her book “Talking from 9 to 5‟, Professor Tannen says:–

“Some of the men I spoke to – and just about every woman – told me of the experience of saying something at a meeting and having it ignored, then hearing the same comment taken up when it is repeated by someone else (nearly always a man).”

This can have a great deal to do with (though of course not exclusively) conversational style differences. Once you become aware of your style, adapting it to others can have major results, though this does come with a note of caution between genders!

Although it is more usual that women adapt their conversational styles to those of the men in a mixed group, they do this in a number of ways. Whilst women might raise their voices, interrupt and otherwise become more assertive in mixed company, they also keep – and even exaggerate – their female-style behaviours, which can backfire.

Whilst smiling and agreeing more often with what others have said is a way to build rapport and good relationships, waiting your turn to speak may mean you miss the chance to make a valid point. It may convey a lack of self-assertion which in turn, somewhat unfairly, can imply an absence of confidence or, worse, weakness. Such assertive behaviour, though, doesn’t tend to work in collaborative environments.

Conversely, research has shown that male-type behaviours in a woman will get a very different reaction, and not necessarily positive! Women in senior positions, and in traditional roles such as lawyers and surgeons, find ways of being firm rather than authoritarian.

Those that are successful with other women, and especially those they manage, maintain female-style behaviours. They take an indirect approach in asking for a task to be done, rather than the authoritative male-style behaviour.

In an ideal world, most of us would be so aware of our own conversational styles that adapting to each others‘ would be easy. As that is not the case, the solution seems first to acknowledge the different styles of communication that can occur between genders (and cultures) and become more aware of our own and our colleagues‘ conversational styles.

Then the next logical step is to become more “gender neutral‘; seize opportunities to combine aspects of our style with that of our colleagues, so that we enhance our communications and interactions with each other.

The ultimate goal being that you are heard; that your meaning is accurately interpreted and that your desired outcomes are achieved. Or as Alice might have replied to the March Hare: “I mean what I say and you’ll know what I mean”.

Can you recall a time when your conversational style may have hindered communication? Is there something you could have said differently that might have avoided misunderstandings and misinterpretations? Could you adapt your conversational style to improve communication and convey collaboration with a colleague?